It is not often that one’s childhood includes sewing lace garments for embalmed foetuses, but such was the early life of painter, Rachel Ruysch.

Ruysch’s father, anatomist Frederick Ruysch, held a deep curiosity for living things. Born in 1638, Frederick was exposed from an early age, to the startling plants and animals that Dutch explorers were bringing back from all corners of the globe. As his collection grew, he rented rooms in The Hague to display the objects. This eventually evolved into a museum filled with over 2,000 specimens that ranged from rare plants and animals, to skeletons and yes, embalmed foetuses that he assembled into startling dioramas. While his presentation of the objects was bizarre to say the least, Frederick was also deeply embedded in the world of scientists, including becoming a fellow of the Amsterdam Surgeon’s Guild in Anatomy, partly thanks to his development of a revolutionary technique for preserving bodies which meant that they could be better studied by artists and scientists alike. He also taught botany at the Hortus Botanicus botanical garden

Rachel Ruysch was born into this world on 3 June, 1664 and grew up not only working as a tour guide in her father’s museum and seamstress to the displays, but also illustrating catalogues of her father’s work, giving her an early exposure to an extensive range of exotic plants and animals.

At the age of 15, Ruysch was apprenticed to Willem van Aelst, Amsterdam’s premier painter of still lifes and by 18, she was producing and selling her own paintings on the open market.

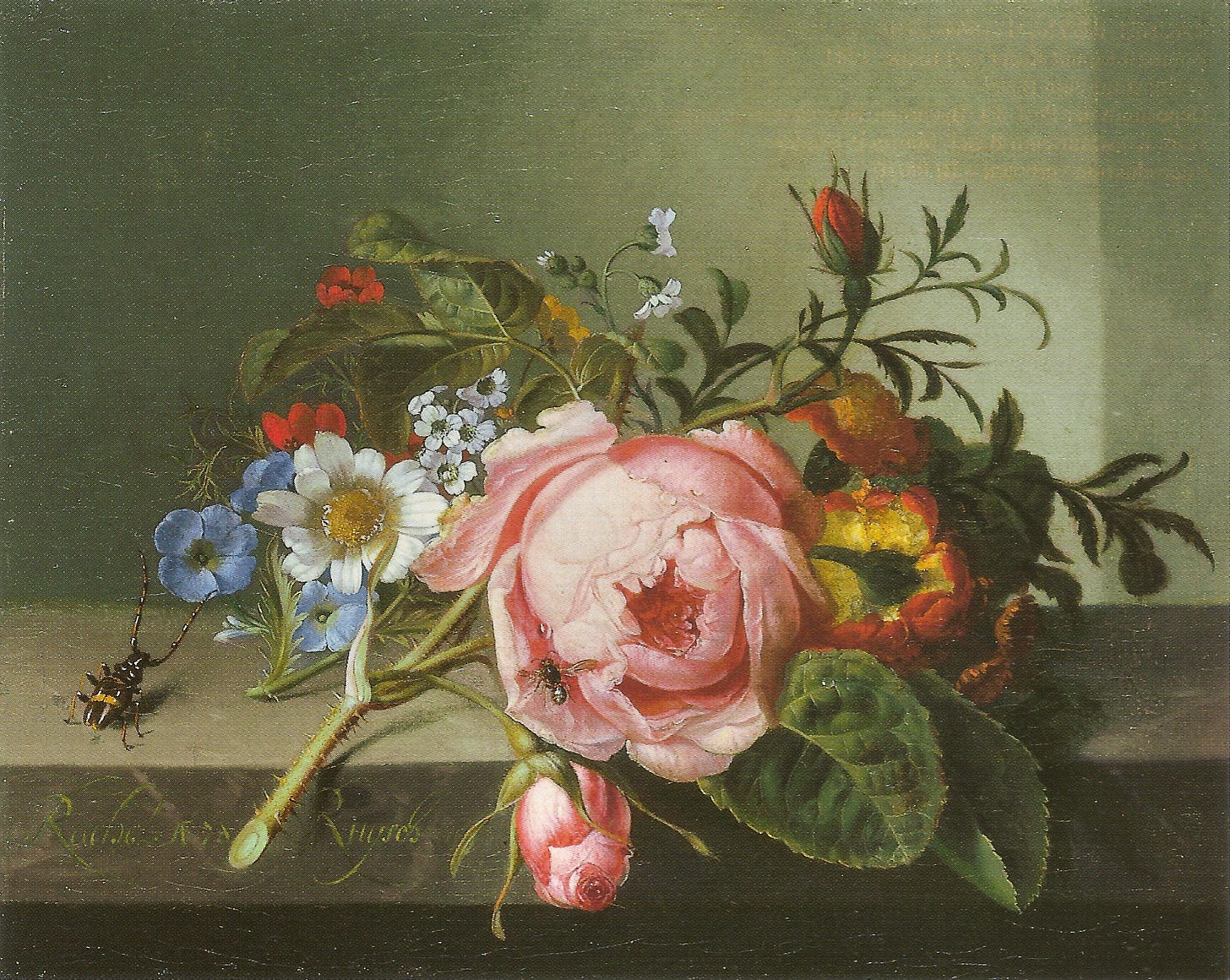

Her still life paintings centre around flowers, insects and small animals, reflecting the influences of her early years. The level of detail - particularly of exotic animals - suggests that she continued to work with and study living and preserved specimens. Her paintings often feature a melding of plants and animal species that would not normally be found together.

Ruysch was also know for using actual plant and animal parts as stamps in her paintings, including butterfly wings and moss.

Ruysch married fellow artist, Jurriaaen Pool, at the age of of 29 and went on to have ten children. Pool’s work was eclipsed by the achievement’s of his famous wife and he appears to have painted little after their marriage. Ruysch was the primary provider in their family.

At the height of her career, Ruysch’s paintings commanded around 1,200 guilders per painting. This would have been equivalent to about 4 years' wages for an unskilled laborer in the 1600s-1700s. By contrast, Rembrandt’s paintings rarely sold for more than 500 guilders. Ruysch painted over 230 paintings throughout her career and was the first woman to be accepted into the Dutch artistic brotherhood, the Confrerie Pictura.

At the age of 44, Ruysch was appointed as Court Painter to the court of Elector Palatine, Jan Wellem and his wife Anna Maria Luisa Medici, in Düsseldorf. Ruysch served the court for eight years until Wellem’s death in 1716 after which she returned to Amsterdam. Her contract in Düsseldorf apparently included a commitment from Jan Wellem to purchase half of her annual output of flower paintings, several of which he gifted to his Medici in-laws in Florence.

At the age of 59, Ruysch won a state lottery, taking home 75,000 guilders and further solidifying her financial status.

Ruysch’s earliest dated work is from 1681 and her last from 1747. She died in 1750 at the age of 83.

Despite the volume of works Ruysch produced during her career and her significant financial and critical success, until recently she has been marginalised in the canon, in favour of male artists, including her Dutch contemporaries. This is part due to the hierarchy of art established in the 17th century by the French Académie des Beaux-Arts (from which women were excluded until 1897).

According to the Academy, historical paintings - including representations from the classics, mythology and the Bible - were firmly in first place. This was followed by portraiture and genre painting that depicted people going about everyday life. Landscapes and still life were well down the list in fourth and fifth place. In the 17th Century, paintings without people were the lowest of the low. While there have been many great still life painters since - both male and female - still lifes are often seen as lesser art forms. Four hundred years later the influence of this (arbitrary) hierarchy still lingers.

As does the patriarchy…

Fortunately Ruysch’s art is now receiving the recognition it deserves. If you’re in the US you can see a beautiful exhibition of her work at the following:

Toledo Museum of Art (Ohio): 13. April – 27. July 2025

Museum of Fine Arts (Boston): 23. August – 07. December 2025

This overview of the exhibition captures some of the incredible detail in Ruysch’s work

The following detail videos from the exhibition are also worth watching. They’re presented in German but all have English subtitles:

Fascinating

I'm truly amazed at the fascinating historical research you do for these posts! Really cool stuff! Keep it up!